In recent memory, video game releases across the spectrum have shown an interesting - if barely noticeable - trend. The tribal demands of players yearning for a stiff challenge have collectively shifted game design up a peg, manifesting itself as an overall increase in difficulty. Seasoned gamers will deny it, but tracking the curve from the 1980s through to today shows a definite resurgence in the masochistic vein of classic game design that many thought dead.

For proof, look no further than roguelike RPGs: a group of games so explicitly influenced by old design and mechanics that it takes its name from a forerunner of the genre. Rogue offered players a randomly-generated game world that was genuinely dangerous. Gameplay was arbitrated by dice rolls before any button pressing even occurred. Arcade veterans will tell you that even chaotic and seemingly random early titles such as Pac Man still relied on extremely basic scripted pathing for their obstacles that anyone could learn to read and avoid. If Rogue felt so inclined a player might die at the first hurdle through no fault of their own - death, of course, being permanent and requiring a meek and weary shuffle back to level one each and every time.

To some this idea sounds terrifying. Players spoiled by the regenerating health mechanic in Halo (and everything else after it) would struggle with the cumulative damage of Doom, let alone having to restart a game upon death. Yet Rogue was not only a success, but also became the mantra for successive generations of hardcore gamers walking the tightrope between risk and reward. The genre thus far culminated in the creation of FTL: Faster Than Light this year, earning massive attention long before launch and a warm critical reception. Predictably, it is just as difficult as its ancestors, adding an infuriating time limit to the random world generation which leaves no room for breathing space if things turn sour (and they will).

Seminal PC sci-fi strategy XCOM doesn't need its own genre to make its influence known in today's market since a cross-platform remake was recently put out with familiarly brutal mechanics in place. Playing in Ironman mode eliminates the ability to save except when exiting the game - another stylistic nod to the roguelike genre. To date, only one person has completed the 2012 release of XCOM on Impossible difficulty in Ironman mode; he was paid to do it during beta testing just to make sure it could be done.

This trend is not limited to just one genre either. In games across the board, Normal difficulty is no longer the middle ground, with difficulty modes extending beyond Hard with apt titles to match, such as Nightmare mode courtesy of Mass Effect. This year also saw the PC port of notoriously frustrating action-RPG Dark Souls, with the depressingly frank subtitle, "Prepare To Die" and proudly advertised with the crippling adversity that would challenge the player.

Why the appeal for games that essentially (and literally in the case of Super Meat Boy) play out as meat grinders, with players dragging themselves back to the start after more deaths than it is realistic to count? Common sense might dictate that random chance is frustrating to a player. It's one thing to fail through human error which can be refined and eliminated, but losing based on chance can ruin the best laid plans with no necessary justification.

In some ways, it's closer to real life than we might think. After all, not everything is always going to go our way. We can't expect each day to be scripted for us with a set solution purposefully put in place by an omniscient designer. Sometimes, luck is not on our side; our decisions are permanent. While comparing life with video games point for point is wholly facetious, the two certainly reflect on each other. The thrill of beating the odds and making it just one more level further than last time is palpable. It's a feeling that more forgiving games - while just as enjoyable in their own right - cannot emulate.

Not only that, but break through the veil of crushing disappointment and defeat to uncover an experience with surprising longevity. Without the need to feel constrained to a tangible twenty hour-plus narrative, difficult games can make a little go a long way. A typical playthrough of FTL might clock in at less than sixty minutes, but when each new game brings fresh challenges and teases of victory, one hour can quickly become six. Beating a game multiple times - on Normal, then Hard, then Kick-You-In-The-Balls - makes a player genuinely feel like they're getting better at a game they love, with the physical evidence to prove it.

A difficult game that doesn't rely on random number generation is a work of art in its own right - the coding carefully finding a sweet spot between "too easy" and "unbeatable". Games like Ninja Gaiden II take a simple genre and engine, then turn it into a beast all of its own. What makes this title genius is how incredibly easy it becomes once it is mastered. But of course, in getting to that stage lies the huge challenge and thus, the game itself.

At the heart of it all, overcoming adversity means bragging rights. The same players who impose self-made handicaps and challenges like the ubiquitous speed run are now rushing out in droves to grab each new game that wears its ludicrous difficulty like a badge of honour for the taking.

Of course this is not new and there have always been hard video games available on every platform. But very recently the propensity for using a game's difficulty as an advertising tool and the fanbase's never-satiated hunger for a challenge has taken on a life of its own. For many people it represents a line in the sand in the market of today, in which games increasingly cater for a family demographic and refuse to be seen as niche. Nobody denies that beating a video game feels good, and is itself an achievement: just maybe there's nothing so bad about losing either.

Thursday, 11 October 2012

Wednesday, 12 September 2012

Gravity Bone

Gravity Bone is that rare gem: the game that absolutely nobody has heard of that receives universal praise and sets the bar for everything that will follow it. So obscure is this game that, intrigued, I played it once three years ago and promptly forgot all about it. It took a second download and playthrough to remind me what a bizarre and intelligent game this is.

Quickly making a name for himself as a powerhouse game developer, Brendon Chung has already tried everything, from a space-based strategy simulator to a birds-eye view zombie survival horror. With Gravity Bone he opted for a simpler approach, building the exotic post-modern cityscape of Neuvos Aires around the skeleton of the old Quake 2 engine. The offspring couldn't be more different from the parent; cuboid-shaped characters speak in muted brass tones while the bright colours of the late 20th Century decor around them seem to glow and throb with heat haze. It is a beautiful and magnetic game world, yanking the player in and revealing its secrets slowly and teasingly.

Truly, this is a game for the gamers, a love letter to interactive storytellers and those who appreciate the craft. The first level gives almost nothing away the second you step off the elevator, giving a real sense of personal satisfaction once you solve the fairly simple sequence that will allow you to proceed. It's made with an implicit understanding that you will decode the gaming logic, thus Chung turns his attentions firmly elsewhere - to the narrative and the stringing along of the player. Once you settle into the pace of the game you begin to be played yourself, living and breathing the story as it races along parallel to your actions. The sense of involvement and attachment to the world is palpable; when no motives for your secretive James Bond-esque espionage missions are provided, you find yourself creating your own and building your own character from the tiny snippets of information you are given. Like Pulp Fiction's glowing briefcase, Chung understands that sometimes the most powerful plot points are the ones that do not get resolved and it leaves this enthralling world open to future exploration.

Unfortunately, it's hard to critically play Gravity Bone without feeling that it could have and should have amounted to so much more. It's also impossible to talk about Gravity Bone without mentioning that it can be finished in twenty minutes or less. The greatest pain about playing this game was having it end just as any other game would have been getting started. Despite how loudly your instincts will clamour to keep playing to overcome the cliffhanger and get your revenge, the lights still come up and the game quietly and smugly retreats back into its shell, taking its joys with it.

Perhaps I am being too kind. I am not suggesting that Gravity Bone is the greatest game ever - it's at least five hours too short for that. Nor will it change the video game industry, no matter how beneficial some developers might find it to play a title with some depth, subtlety and genuine artistic direction. However, this is still an incredibly written, enjoyable and original game made by just one man and I feel that must count for something. Anyone who knows anything at all about game design will have at least one moment in Gravity Bone that they truly appreciate for being a stroke of absolute genius.

In the end, Gravity Bone is comparable to a £30 starter course at a fine French bistro: elegantly presented, minute in size, gone in a flash, but one of the best things you ever tried. If you're intrigued, it can be downloaded free from the developer.

Monday, 20 August 2012

Slender

The name Slenderman will be instantly recognisable to some and yet totally alien to others. An urban legend for the internet age, the eerie character has exploded in popularity over the last few years, resulting in dozens of mockumentaries, eyewitness accounts and at least one video game. Swap varsity jacket-clad teens for amateur filmmakers with camcorders and the hook-handed mental patient for a supernaturally tall figure with a ghostly pale featureless face: a premise that sounds a touch ridiculous until the paranoia sets in and you begin to imagine the Slenderman silently watching you from a window or maybe even the shadows in the corner of your room. That's how it starts. After all, according to the myth: when you become aware of Slenderman, he becomes aware of you.

I'll be the first to admit a macabre fascination with the eponymous otherworldly stalker. There is something deeply unsettling about him/it - although, personally, I blame the resemblance to arguably the most terrifying fictional monsters from my childhood, the Gentlemen from Buffy the Vampire Slayer. However you look at it, the Slenderman zeitgeist has never been stronger. Solo developer Mark Hadley ran with the concept and created one of the simplest and scariest games in recent memory.

Slender is a first-person adventure title in which the player explores an area of forest searching for clues in the form of notebook pages that allude to a mysterious being. The physical mechanics of the game are straightforward enough, right down to the torch beam that follows your gaze around the screen as you pace forward. But the cookie-cutter veneer of this game hides a truly dark heart.

Everything in the game world is designed and placed with such precision and purpose that it cannot fail to induce a sense of terror immediately upon starting and before any move has been made. The darkness around the player is palpable, the torchlight only illuminating the next tree in front and little more. It's only then that you realise the torch battery is limited and must be conserved, and without that meagre amount of light, it suddenly gets a whole lot darker.

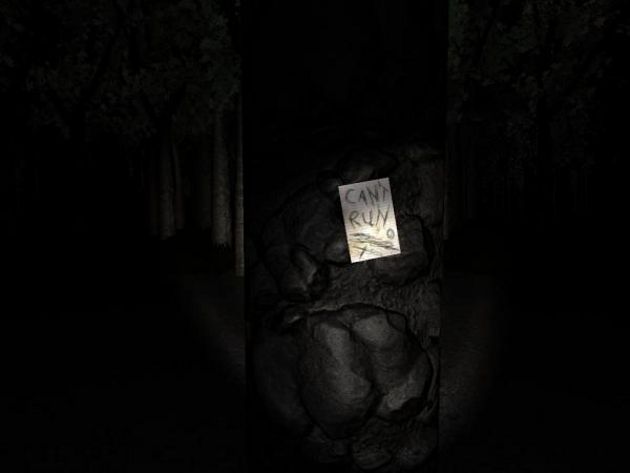

Gathering notebook pages allows you to read archetypal scribblings like "can't run" and "don't look", but simultaneously brings the omniscient Slenderman closer to you. Catching fleeting glimpses of a lanky black body and white face in the distance is bad enough, but coming upon an abandoned car and seeing him there inside waiting for your arrival is the stuff nightmares are made of. With his increased proximity comes the deterioration of your character's sanity and the higher likelihood of sudden scares. The game achieves so much with so little: even simple camera tricks are applied to make apparitions vanish behind one tree only to reappear from behind another - much closer than before, naturally. The admittedly short game can end in one of two ways, neither of which I'll go into, but suffice it to say you will not be clamouring to play again. I say this not out of contempt for the game, but to applaud the atmosphere of total unease, insecurity and dread.

Perhaps most notable and most effective feature of the game - and I hesitate to ruin the surprise - is the distinct lack of a pause or menu button once gameplay has started. I myself particularly enjoyed this little touch immensely as I desperately tried to stop the horrors on the screen and return to the safety of my desktop only to discover this was literally impossible. Once you jump the fence and land in the woods, you're all in. Frenzied hammerings of the escape key will do nothing except bruise your finger and probably drive you over the edge into total insanity.

It's testament to the power and effect of Slender that countless fan videos have gone up capturing the reactions of unsuspecting new players. Indeed, this is a game that wholly deserves being entered with no expectations and no knowledge of what the hell it is hiding just out of range of your torch. Slender definitely warrants at least one playthrough's worth of your time. It's free for Mac and PC on the official site. Just remember: now you know, so does he.

Saturday, 11 August 2012

Organ Trail

DAY 1

8am: We load up the station wagon with as much fuel and food

as we can carry, determined to escape the nuclear wasteland of Washington DC

and make the exodus to safe haven in Oregon. Along for the ride is my team of

seasoned zombie-battling veterans – riding shotgun is Ash, and crammed

awkwardly into the back are Shaun, Chris and Jill. We hit the road just as the

first bomb detonates over the capital and drive uncertainly forward.

9am: My team is already complaining about being thirsty. I

grip the wheel tightly. It’s going to be a long trip.

1pm: The car breaks down. Shock and awe give way into total

rage when I realise that we stocked the car with enough fuel to drown a

dinosaur but not a single spare tire. Balls.

2pm: Miraculously the first car that drives by offers us a

tire in exchange for some food. We make the trade and cruise off with renewed

spirits.

6pm: Leaving Pittsburgh we encounter our first group of

zombies. A small, disorganised bunch; I gently toe the accelerator and we try

to sneak past them. Predictably, our car is not made for sneaking and the hoard

attacks us, stealing food supplies and biting Jill. She claims to be fine, but

I’m already expecting the inevitable.

DAY 2

3am: We pass a gravestone jutting out of the earth by the

side of the road. Naturally I want to drive right past this unremarkable sight

but Chris insists on going in for a closer look. A zombie bursts from the

shallow grave, surprising no one. I quickly dispatch it with a handy headshot

and kick Chris back in the car. I’m in a mood with him now.

4pm: We lose another tire on the car. I go into a nearby

field and have a bit of a scream. It could be a while before we see another

person, let alone one with bartering supplies.

DAY 3

1am: A crushingly boring evening by the roadside pays off. A

stranger sells us a tire for just $8. Clearly the heat and radiation have

gotten to him. We drive off before he changes his mind.

7am: The car battery goes flat. Clearly this is no station

wagon but my old Vauxhall Corsa judging by its horrendous reliability. We jump

start the car and roll away, heading for Chicago. Frankly I’m amazed the

vehicle hasn’t caught fire at this point.

11am: The car catches fire. Luckily the flames dodge

everything except our money – which I’m pretty sure was in my wallet and in my

pocket at the time. Regardless, we’re now broke.

DAY 4

2pm: The engine warning light comes on. I swear this car is

trying to get us killed.

5pm: As we limp into St Louis, Jill falls into a coma. Her

wound has gotten the better of her and the first signs of zombie infection are

spreading outwards from the bite. I hesitate for a few moments before putting

her out of her misery. Shaun observes that at least we have fewer mouths to

feed now. Nobody finds it funny.

DAY 5

3am: Outside St Louis we run into another, larger, pack of

zombies. Perhaps in vengeance for our fallen comrade, we convert the car into a

rolling death-mobile and unleash a storm of lead into the crowd. We make it

through safely, feeling a little vindicated.

DAY 6

4am: We follow vultures to a supply of food since our

stockpile is dangerously low. I consider protesting against eating the diet of

winged scavengers but nobody else seems to mind.

1pm: The road ahead is blocked with hundreds of derelict

cars. It takes us the better part of an hour to navigate round them. While

we’re mucking about with the car, Shaun simply wanders off. We lead a brief

search but he is never seen again. His fault, not mine.

DAY 7

1am: We make it to Dallas in the early hours of the morning.

Our elation is cut short when we work out that it’s a six hundred mile leg to

the next landmark. That’s an awful lot of time for something to go badly wrong.

3am: We prise a tire off a broken-down car. It’s usable, so

we take it with us, preparing for the next vehicular calamity.

4am: We are held up in the road by road warrior wannabes.

Their car must be in a worse state than ours because they steal our new spare

tire and leave the fuel and food. Easy come, easy go.

DAY 8

12pm: In the space of two hours while I’m away from the car

scavenging for food, Chris comes down with dysentery and Ash breaks his leg. I

have no medical kits to heal them so can only look at them in a sort of

sympathetic way and hope they recover.

DAY 9

9am: We barely make it to Albuquerque. Ash has recovered his

health by ravenously consuming every morsel I can scavenge but Chris is

incapacitated with sickness. With no medicine and nothing to trade we try to

get some sleep in the town but Chris dies. As always, I blame the car.

11pm: Three hundred miles from Las Vegas, Ash and I finally

run out of fuel. We fall into a routine of scavenging for food and desperately

holding out for passing traders to give us something we can use. I know it’s a

matter of time before we either starve to death or eat each other.

DAY 11

2pm: I secretly consider killing Ash just to stop him eating

all my food. Good god, the world has been ended for less than two weeks and I’m

already turning into a sociopath.

5pm: We trade some food for fuel and sputter our way down

the road. It’s agonisingly slow progress. We barely even speak to each other

now. There’s nothing to say.

DAY 13

6am: Dawn is breaking. The sun is reflecting off the

millions and millions of bulbs in the Vegas skyline, making them look like

they’re shining. I know they’re not; the power went out days ago. Behind me on

the flat desert road, I can still see the low mesa where I dumped Ash’s body.

Fewer mouths to feed now! I worry that the corpse is attracting more zombies.

I’m guessing that’s what all those black dots are shuffling their way down from

the yellow ridges and gullies and heading towards the car. I remember being so

worked up by a simple punctured tire. Seems like forever ago. Really puts

things in perspective. We had a good run though. Here’s to the end of the

world.

You can live your own post-apocalyptic road trip by playing Organ Trail here for free.

Saturday, 30 June 2012

De Blob

As an inspirational story charting the success of an indie video game project, it's hard to beat De Blob. The original PC version was created in just four months by a team of less than ten students at a Dutch university. Now, a console port is widely available with a sequel on its way. Its easy to see why this title was snapped up and turned into a blossoming franchise, since the project that started it all was published as freeware and remains active for download today.

De Blob has a streamlined

plot: you play as an amorphous alien shortly after crash-landing right in the

middle of the city of Utrecht. Worryingly, the city is bland and washed out,

with the buildings appearing as pale blank canvases. Faceless government drones

scuttle through the streets, absorbing the colourful inks from the world to

further their nefarious schemes. As the Blob, it's your mission to reclaim the

colours into yourself, making your whole body a giant rolling paintbrush and

applying inks onto the buildings and other surroundings with a simple touch.

Picking

up citizens of Utrecht gives you various primary colours to work with, while

picking up groups of people results in new shades. Grab too many, and you'll

eventually end up with a muddy brown mix. Alternatively, absorb one of the evil

G-Men and your body will turn jet black, rendering you useless and forcing you

to locate a river or fountain to purge yourself of the taint. Points are scored

by painting buildings, as well as other objects such as trees and billboards.

Bonuses occur when city blocks are fully painted, or when key landmarks - all

modeled on the real city - are recoloured to their original state. As an added

twist, certain locations can only be reached through a series of careful ramps

and jumps: deceptively difficult when dealing with the physics of a rolling

blob.

For

a game made to such incredible time constraints on zero budget, the technical

side of De Blob is

astounding. Graphics are simple, but not overly so, and indeed would look right

at home on the Nintendo Wii (probably not by coincidence since the console

claimed the rights to the franchise shortly after release). The colours are the

star of the show and are just as bright and vibrant as you would expect. There

are neat little touches everywhere, such as how the Blob leaks ink wherever

he/she/it rolls, leaving a permanent trail on the streets. Aesthetically it's a

good effort, but it also serves as a trail marker of sorts, indicating which

areas of the city you've yet to explore.

The

controls are, initially, a bit of a hurdle to overcome, especially for players

eager to dive right in and begin splashing colours around. The Blob rolls

around according to momentum, so stopping him is much harder than getting him

started. It can also make some of the sections of the game frustrating when the

Blob misses a ramp and rolls off a rooftop for the fifth time. However, this is

not an intensive game. It does not take long to adjust to the mechanics and

it's easy to continue playing once you've begun. Players that like having

objectives and goals might be deterred though; when a game is quite literally a

blank canvas there is very little direction and no concrete achievement to

speak of other than gaining points. The game can be completed with no more than

an hour or two of dedicated play, after which it's a matter of starting all

over again with a new, blank map. This naturally limits the lifespan of the title,

but considering it was only created as a school project it hardly seems fair to

berate it for lacking the shelf life of Skyrim.

De Blob is a masterclass on how

original gameplay and unconventional thinking can result in a simple yet highly

playable title that not only stands up on its own, but also forms the basis for

a growing franchise. To try De Blob yourself

and see where this quirky, colourful adventure began, you can download it here for free.

Monday, 21 May 2012

The Binding of Isaac

The twin-stick shoot ‘em up

is a genre synonymous with flashy effects and fast-paced arcade style gameplay

as exemplified in titles like Robotron

and the phenomenal Geometry Wars. The Binding of Isaac dares to plunge the

twin-stick shooter into the bold new territory of survival horror. The results

are surprising, if a little hard to stomach – for all the right reasons.

The Binding of Isaac draws its story influences directly from the Bible,

and tells a macabre tale of a mother driven mad by evangelical TV who, obeying

the voices in her head, plots to murder her young son in the name of God. Isaac flees to the cellar to apparent safety but must then confront a

legion of demons conjured out of his darkest nightmares using the only weapon

at his disposal: his tears. It’s a grim tale that sets an uneasy tone for the

game right off the bat. There is no ray of sunshine to be found. Gamers who

dare will find a brutal and uncompromising road ahead of them.

The game unabashedly models

its interface from the seminal Legend of

Zelda, and indeed there are similarities to be found within the game

itself. However, like the best survival horror titles before it, careful health

and inventory management is nothing short of essential. This is a game where

one stray hit can spell disaster in the long term, leaving you crucially short

of vitality at the end of a long boss battle. Special items grant different

abilities and effects, but some are only temporary and often it is impossible

to determine an object’s use right away.

The risk-reward balance is perilous, and often leaves the player feeling as helpless as the weeping hero on screen. Make no mistake, the designers do not want you to succeed. You will face gruesome enemies, each design more Lovecraftian than the last. Some of the game’s basic enemies include walking corpses that continually utter a throaty death rattle and spew blood from a neck wound. The boss models are no less impressive; one fight pits the player against two conjoined twins – one huge and bloated, the other an atrophied foetus. Every enemy has a unique attack pattern and requires an intelligent approach, all the more so when multiple enemy types fill a room and only grant escape once defeated.

It’s in extended combat

that The Binding of Isaac shows off

one of its most intriguing features: physics-based shooting. The movement of the

player directly affects the behaviour of the projectiles flung at your foes,

thus moving perpendicular to your shots results in a bending effect, allowing

the most expert players to hit enemies around corners or in a hidden weak spot.

The system works beautifully. It’s a great reward for perseverance and practice

and the results will be seen when, after each inevitable death, you find

yourself making better and better progress.

Exploring the dark, haunted

corridors is kept fresh with each successive playthrough thanks to a randomly

generated map; monsters, items and even bosses appear in different locations

each time. Unfortunately, this leads to annoying glitches making some treasures

inaccessible beyond bottomless pits or walls of stone. The replay value of the

game is bolstered with unlockable characters that become available after

reaching milestones with Isaac. These new characters – all Biblically derived –

possess their own stats and special abilities and drastically alter the play

style of a new game.

The Binding of Isaac is aimed squarely at a certain demographic of gamer:

a group that will not shy away from a challenge and does not expect to breeze

through a story in one playthrough. This is a game that rewards endurance,

practice and adaptation. However, brave the initial difficulty and beyond lies a deep

shooter with plenty to offer for a very low price. With the Wrath of the Lamb expansion pack just

days away, this is a title well worth consideration.

Thursday, 29 March 2012

Bastion

“The kid gets up,” intones the omnipresent narrator, just as I nudge the control stick to stir my character from his bed. It’s the once-upon-a-time that will begin this unique story: one that I am writing as I play. I can already tell that Bastion will be something special.

A product of fledging developers Supergiant Games, on paper this action RPG looks wholly unremarkable, even abhorrent to a gamer who’s sampled the genre before. A mute boy (strike one) must journey through a shattered land populated with monsters (strike two) utilising a variety of weapons including a sword, a hammer and a bow (strike three). However Bastion overwhelmingly proves that a story truly resounds in the method of its telling.

Indeed, “story” is the key word here. Every movement, every choice you make – every accomplishment and every failure – is narrated as it happens. When you arrive at a crossroads and pause for a second to debate which direction to go, the narrator calmly observes that “The kid ponders a spell, to get his bearings”. When you do start off on your way again, it’s to the tune of “The kid decides to head north first”. It’s startlingly effective, and it feels like every choice you make is the way it always had to be. It doesn’t bear thinking about what would have happened if you had simply run straight through that junction: the actions that you naturally took as a player created this story that is ongoing even now. In this way, Bastion truly shines, offering a world that’s just as governed by action and reaction as our own. No choices are punished, and that just makes it even more rewarding to proceed as you see fit, rather than choosing x response or going to y place first just because it’s beneficial. What’s more, the narration never tires or grates, and never becomes intrusive. Like the rest of the game, it feels natural – just another part of this world you’re in.

The technicalities of the game are no less impressive. Calling the visuals “graphics” feels almost insulting to their level of quality. Each piece of scenery has been meticulously hand painted to a phenomenal standard. You would hardly imagine that this is a world post-apocalypse, so vibrant and bursting with life are the backdrops and vistas that construct themselves around you with every step you take. This stylistic choice not only gives a sense of natural direction to the game, ensuring that the player is never lost or overwhelmed; it also reinforces the idea that this is a story in the process of being told as buildings and trees literally spring from nowhere as the narrator describes entering a deserted city square or muck-flooded swamp.

The gameplay is as smooth and polished as the art, with not-overly complicated combat making up the bulk of the interaction. However, it’s in the eponymous Bastion that the designers and writers really flesh out the “role play” in this role-playing game. Trinkets and mementoes from your travels can be examined with companions, offering windows into the rich backstory. Cleverest of all is the manner in which standard features such as the difficulty level of the combat or achievements are disguised as part of the game world. Take a god as your patron at the pantheon, for instance, and the hostiles all get a little a bit stronger. The more gods you worship, the more augmentations your enemies will receive, but the same applies to your experience and monetary rewards. Because Bastion never loses its sense of verisimilitude then neither does the player, and it makes for an incredibly engrossing and rewarding experience.

Bastion is without a doubt one of the best gaming titles in recent memory – it’s innovative, fresh, and bursting with new ideas in a slightly stagnated market. But it stays true to its roots of classic top-down 16-bit titles with its quirky designs and straightforward combat mechanics. It’s destined to be a classic in years to come. I’ve told you how the story begins, but I wouldn’t dream of telling you how it ends. It’s far too much fun discovering it for yourself.

Insert your coin: welcome

So this is Run! Jump! Shoot!, a blog that hopefully some people will read.

My aim is to cover a different range than other websites (and the few magazines we have left) and instead focus on the lesser-known, under-the-radar, independent games. The best thing about games of this type is that they're often very easy to come across. Many get released as freeware to find a wider audience; those that don't very rarely carry the £40 price tag attached to blockbuster releases.

Indie games, unlike the music of the same name, are defined not by style but by substance. Indie games originate from small developers, some of whom will never make another game beyond their debut. Although it's true that indie games share a lot of common motifs they're also vastly different from one title to the next. It's my hope that my readers discover some new games to try through my blog, rather than simply reading one guy's opinions in a sea of thousands about the newest Call of Duty.

Have fun boys and girls.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)